26 November 2017 —

At some point, any enterprise project will probably need a message queue.

A message queue is used to publish information (usually known as messages) that a different “node” (usually known as worker) will consume in order to perform a specific action.

It is frequently used in web applications to pass information to background workers that consume the queue and perform long tasks, but it is also an important part when applying concepts like Event Sourcing to your architecture.

It is also really important when working with microservices, since it is a way to enable data exchange between each service.

Whatever the case, it is very likely that you will eventually need to decide which message queue to use.

Why AWS Simple Queue Service

In my company we had to decide this some time ago.

We started testing different services, seeing what their strengths and weaknesses were.

If I remember correctly, we tested RabbitMQ, Beanstalkd, Redis and AWS Simple Queue Service (SQS from now on).

The conclusion was that RabbitMQ is the one with the more features, by far. However, it is also the most complicated to configure and interact with.

Also, we would have to maintain the RabbitMQ clusters ourselves (the same happens with Beanstalkd).

Since we work with AWS, we decided to give SQS a try, and its simplicity convinced us.

It is super simple to create a new queue, and using one of their SDKs, you can interact with it in minutes.

Also, the price is absurdly cheap. It is virtually free for “small” amounts of requests (and when I say small, I mean that performing 1 request to their API every 20 seconds during 1 year costs about $0.30 at the end of the year).

It is by far cheaper than maintaining your own instances with a different service, and I’m not counting the cost in time you will have to invest in maintaining those servers.

The “small” problem with SQS

One of the most interesting features with RabbitMQ is that you can open one socket with the queue server, and once a new message gets in, the worker is “notified” and the message can be consumed. This way, you have a process which is always running, listening for a queue, and processing messages as soon as possible.

This is usually the desired behavior. You don’t want any delay on processing messages (or the delay should be as short as possible).

On the other hand, SQS bills by API request. This means that the worker has to manually check if there’s any message in the queue, in small intervals.

Our first approach was configuring cron jobs in our workers, so that they could check if there were any message in the queue, and process all of them, if any.

This was problematic, since it applies a delay of up to one minute (you can’t configure a cron to be run with an interval smaller than that), which is not desirable, particularly when the job takes 5-10 seconds to complete. Adding an extra 600% of waiting time can affect the user experience, or have other side effects, depending on the task.

The long polling to the rescue

The first solution that came to our mind was making the workers run requests on an infinite loop, but that’s not a very clean approach, and will result in our workers being at a 100% of CPU usage all the time.

We started investigating and found out about a feature in SQS called long polling. It lets you tell the queue to wait up to 20 seconds before returning a response, if the message queue is empty, and if during that time a new message enters the queue, return a response immediately.

Using it, you can make a worker continuously perform requests at 20 second intervals, but if a message is in the queue, the response will be returned immediately.

The final behavior is very similar to a socket, in which you can process a message as soon as it enters the queue, and the worker does not consume any resource while it is waiting for a response.

Configure a queue with long polling

There are two ways of configuring the long polling. You can do it in AWS, and make the queue always have it, or you can do it client-side, and add a WaitTimeSeconds param with the time in seconds (with a maximum value of 20 seconds).

The second option is very easy to implement when using any of the official SDKs, and is more flexible, since you can decide when to wait for a message and when to fail immediately when the queue is empty.

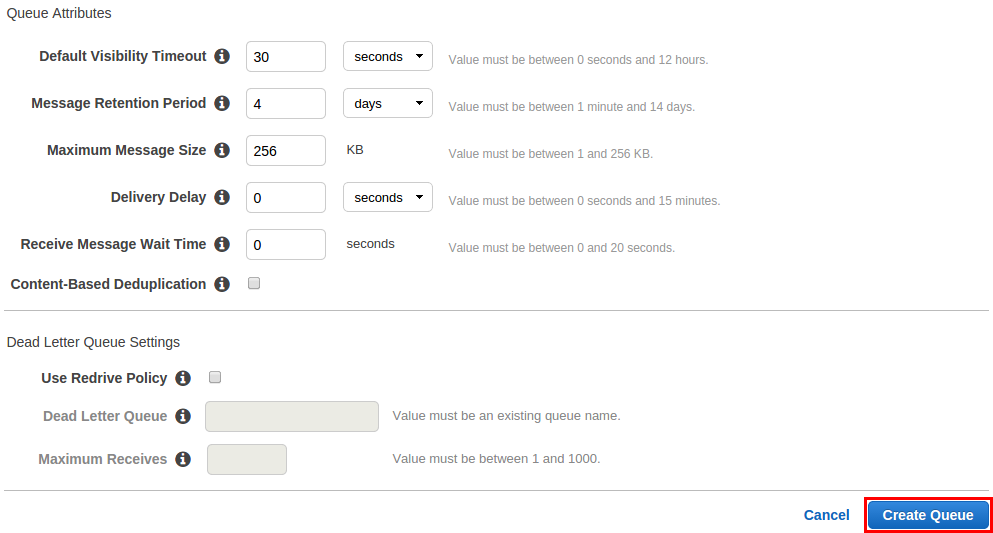

The first one is very easy too. Just set a value for the “Receive Message Wait Time” param, when configuring the queue.

That should be all, but there’s one important consideration.

If you have several workers consuming the same queue with long polling and one message enters the queue, all the workers will receive it until one of them deletes it. This is usually problematic, since it could lead to one task being processed more than once.

In order to prevent this, you should set a small value in the “Default Visibility Timeout” param, which tells SQS to deliver the message just to one consumer, and wait that amount of time before delivering it to the rest.

This way, you can make one of the workers receive the message, delete it from the queue, and then process it, and that will prevent other workers from receiving it.

Usually, setting a value of 3-5 seconds should be more than enough for the first worker to remove it from the queue. However, if you expect your workers to need a longer time, just increase the value.

Remember, that value will delay delivering the message to all the workers but the first that gets it.

Conclusion

We have seen an efficient way of working with SQS, the most simple, yet powerful message queue.

If you have more complex needs, it might end being too simple, but if not, it is possible to tweak it enough to use it on large applications and services.